Updated January 23, 2022 at 8:33 AM ET

The Sunday service at the Patriot Church in Lenoir City, Tennessee starts out like a lot of evangelical worship: hands aloft, Bibles in laps, full-throated singing about Jesus.

When Rev. Ken Peters picks up his wireless mic, the service takes a sharp rightward turn.

"Don't let the mainstream media or the left tell you that we were not a Christian nation," he intones, prowling the altar in an anti-abortion T-shirt. "You know why there's churches everywhere and not mosques? Because we're a Christian nation!"

"Amen," responds the congregation, with gusto.

The sermon, titled "How Satan Destroys the World," zigzags between familiar grievances of conservative Christians, such as abortion and transgender people's rights. But what makes this church different, and others like it across the nation, is its embrace of the secular agenda of the far right. They believe that masks and vaccinations violate religious freedom, that the participants in the Jan. 6 capitol riot were proud patriots, and the Biden administration is evil and illegitimate.

"You know he's not the most popular president in America," Peters preaches, still obsessing on election results 14 months later. "How many Biden parades did you see? Yet he beat Trump with 70 million? Give me a break. We know something's up."

Christian nationalists believe that America is Christian and Trump is their best hope to keep it that way

If anyone thought that Christian nationalism would decline with President Donald Trump out of power, they were mistaken. Christian nationalists believe, in general, that America is Christian, that the government should keep it that way, and that Trump was —and is— their best hope to accomplish that.

This movement of ultra-conservative, politicized churches is apparently on the march, though there are no firm numbers because the congregations are mostly nondenominational. The belief system provides a godly underpinning for right-wing activism in venues like school-board elections, anti-vaccine protests, and the Jan. 6 attack on the capitol.

"This is a spiritual battle. It's good versus evil," says congregant Jim Willis, after the service. He's a 72-year-old retired army colonel and software salesman, who wears on his lapel an American flag inside of a Christian cross. "And, unfortunately, evil has taken charge."

Willis says he and his wife fled California because of heavy-handed pandemic restrictions and headed to Tennessee. He says the Holy Spirit led them to the Patriot Church, which is not afraid to jump into the fray.

"We know what (the enemy's) agenda is," he continues, with a steely gaze. "Their agenda is to close down churches, to get rid of religion permanently in this country."

When it's pointed out that Joe Biden is a lifelong Catholic who attends weekly mass, Willis responds, simply, "No he isn't."

In this partisan fissure in which America is living, imperviousness to facts is a sign of the times.

Outside on the walkway, Murray Clemetson stands with an armful of hand-made signs he brought to church, such as, "Set the DC Patriots Free" and "We Are Americans, Not Terrorists." The law-school student and father of three —all home-schooled— was at the "Stop The Steal" rally in Washington, D.C., last year.

"Donald Trump represented what we stand for as a nation"

"The only insurrection that happened on Jan. 6 was by the agent provocateurs, paid actors, and corrupt police and FBI," he says, disputing all the evidence made public in the more than 700 criminal cases that the rioters were Trump fanatics.

Clemetson would be among the 84% of white evangelical Protestants who voted for Trump in 2020, according to the Pew Research Center. He is asked if the Patriot Church is a Donald Trump church.

"I think it is a Donald Trump church," he answers. "Donald Trump represented what we stand for as a nation. You go to flyover country and people have good moral values. They love the Lord and they want the best for the country. And that's what Donald Trump tapped into. That's what he represented."

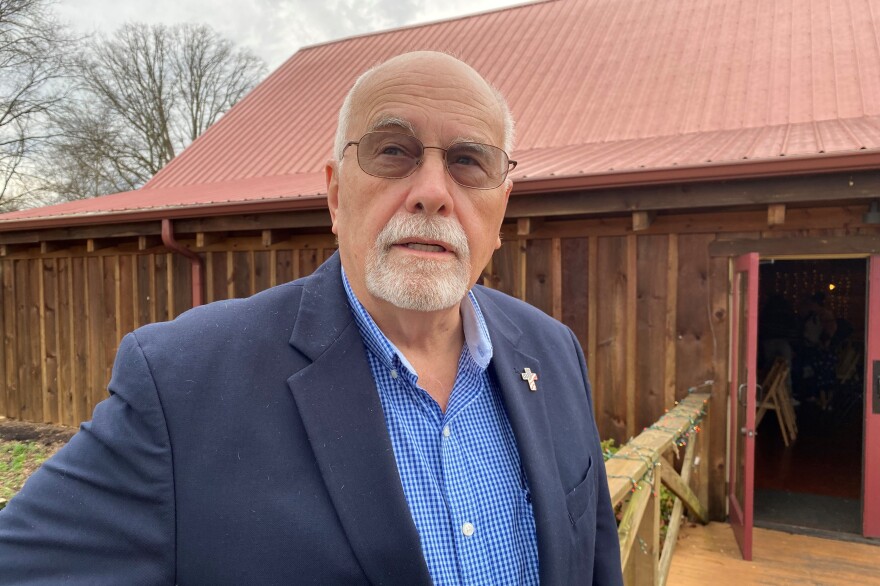

The next morning, Ken Peters is waiting inside his church with a cup of coffee for a sit-down interview. He's a 49-year-old, fifth-generation minister who grew up in the Pacific Northwest, and one of the few MAGA church leaders who welcomes journalists.

The barn-like Patriot Church, with the giant American flag painted on the roof, has prospered. There are currently about 350 church members in the four campuses, in Tennessee, Virginia and Washington State, with two more locations underway.

Peters believes so fervently that his candidate won the presidency that he exhorted his flock to go to the U.S. capitol on Jan. 6. He says 15 to 20 parishioners attended the now infamous rally, though none entered the capitol building. Peters himself addressed protestors on Jan. 5.

Continuing a theme from his Sunday sermon, he says, "We consider the left in our nation today to be a giant bully ... And when there is a bully on the schoolyard and somebody rises up and punches back, 'Hallelujah!' So we are thankful for Trump."

"But you know what? If Trump passes away tomorrow, God forbid, does that stop us? Does that slow us down? Not one bit. We'll be looking for the next guy to lead the way."

The rise of Christian nationalism is both a symptom and an accelerant of the polarization that afflicts America.

And there is more and more pushback. Beginning last year, more than 24,000 national church leaders, clergy and lay people have signed a statement that condemns Christian nationalism as a distortion of the faith and idolatrous of the former president. That letter, and the proximity of the Patriot Church, motivated one congregation just up the highway to take a stand.

Church of the Savior —a liberal, inclusive congregation that's part of the United Church of Christ— is perched on a bluff overlooking Interstate 40 in Knoxville. A sign out front reads, "Immigrants & Refugees Welcome." Senior pastor John Gill stands at the pulpit on a recent Sunday and starts his sermon this way:

"I think many of us believed and hoped that the fever of misinformation about the election and the pandemic and all the related efforts to undermine democracy in our nation would somehow abate. But that's not happening."

Indeed, he says, things have gotten worse.

"It's difficult for me to understand how they can claim to be patriots," he continues, "when they reject ... the first amendment that prohibits the establishment of state religion."

Finding common ground with Christian nationalists is difficult

The youth minister at the church is 58-year-old Rev. Tonya Barnette. She says, in an interview, that Christian Trumpism has also broken out in the Pentecostal churches where she grew up in Appalachia.

"My family would go to the Patriot Church if there were one around Big Stone Gap, Va.," she says. "The churches they go to teach the same things."

Barnette is lesbian, and she says her sexuality and her progressive religion are still rejected by some of her family members in the coal town of Big Stone Gap. She says she understands why people in the Patriot Church are scared.

"I think it's some kind of fear of difference," she says, "fear of me as being different, fear of the nation changing so that it's not white, cis, straight, male Christians in charge only. And it's moving more toward people who are different."

Barnette says, in her view, Christian patriots are completely missing the true message of the gospel.

"Wanting to gain power as Christian nationalists is in direct opposition to what Jesus taught. The goal is compassion, kindness, and care for the other. That's what Jesus did."

A 55-year-old librarian and Church of the Savior parishioner named Ed Sullivan says, "I mean, there's nothing new about Christian nationalism. It's been part of this country's history for a long time. Decades."

As Sullivan observes, the Bible has been thrust into conservative politics long before the Patriot Church. In the 1980s, Jerry Falwell's Moral Majority helped to get Christians involved in politics. In the 1950s and 60s, Billy James Hargis promoted his Christian Crusade on more than 750 radio and TV stations.

"But the Patriot Church movement is certainly the most extreme manifestation of that that we have today," Sullivan says.

Is there any way, he is asked, to narrow the chasm that separates these two churches in Eastern Tennessee that both profess to follow the same Jesus?

Sullivan answers, "If they (Patriot Church) view anyone who dissents with their point of view as evil, or the enemy, or of the devil, I really don't see how there's any kind of common ground."

When the same question is put to Rev. Peters, he says the last thing they want is a civil war. "We don't want bloodshed. We want to live in peace and stay united ... That's going to be very difficult."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.