The story comes from KCLU’s podcast The One Oh One. You can listen to the full episode here.

There are mountains, creeks, canyons and hollows all throughout the United States that have the word negro in their name – close to 600 of them to be more precise. There’s Negro Canyon in Arizona, Negro Hollow in Kentucky and Negro Creek right here in Ventura County, California.

Before the 1960s these places all had a different name – not negro, but the n-word. In response to the civil rights movement the Department of Interior made a wholesale change to all place names containing slurs for Black people – they exchanged the n-word with negro.

Within ten years or so, though, the word negro would also come to be seen as derogatory and offensive in most cases. So, since the 1970s the word is rarely used.

But, a site in our neighborhood – a mountain just off of Kanan road near Agoura Hills – retained that new Department of Interior name for decades. It was originally named n-wordhead mountain and then became negrohead mountain.

In recent years, a group of locals - mostly white folks - set out to change that.

In 2010 they succeeded in a campaign to rename the mountain for the Black pioneers it was presumably originally named after.

In this piece, we look at the shedding of one racist place name in our neighborhood, and how it revealed the hidden history of a Black pioneer named John Ballard.A mountain that used to have a racist name

Nestled in the Santa Monica Mountains, about halfway between the Pacific Ocean and the 101 Highway near Agoura Hills is a mountain. For the couple whose property sits at the base of this mountain it’s a spectacular site.

“One of the things that we always loved about the mountain is the sunsets. The mountain turns the most remarkable colors. It is just magnificent. And it's one of the things that drew us to it and keeps us here,” said Paul Culberg.

Culberg has lived next to Ballard Mountain, as it is now known, with his wife Leah for 45 years.

At sunset the mountain reflects the sky and turns gold, orange and purple, they say. And in the winter, when there’s a decent amount of rainfall, the mountain is covered with waterfalls gushing over different rock faces.

For Leah the mountain is more than visually beautiful – it holds memories of its past and present.

“When we look at the mountain, I think, you know, I think of the Ballard family and I have nothing but warm feelings for them,” said Leah Culberg.

The renaming of this mountain took place over a decade ago. The push to get the name changed from Negrohead Mountain is reflected in a new documentary released by the National Park Service this year.

To understand what that journey entailed, and the hidden history it revealed, we have to leave Ballard Mountain for a moment – we’ll be back – but for now we go to Moorpark College to meet Patty Colman, a local history professor.Revealing hidden history

“I have probably the best job In the world. I get to come to a beautiful campus every day And I get to spend my time with students. I get to talk to them about history,” said Patty Colman.

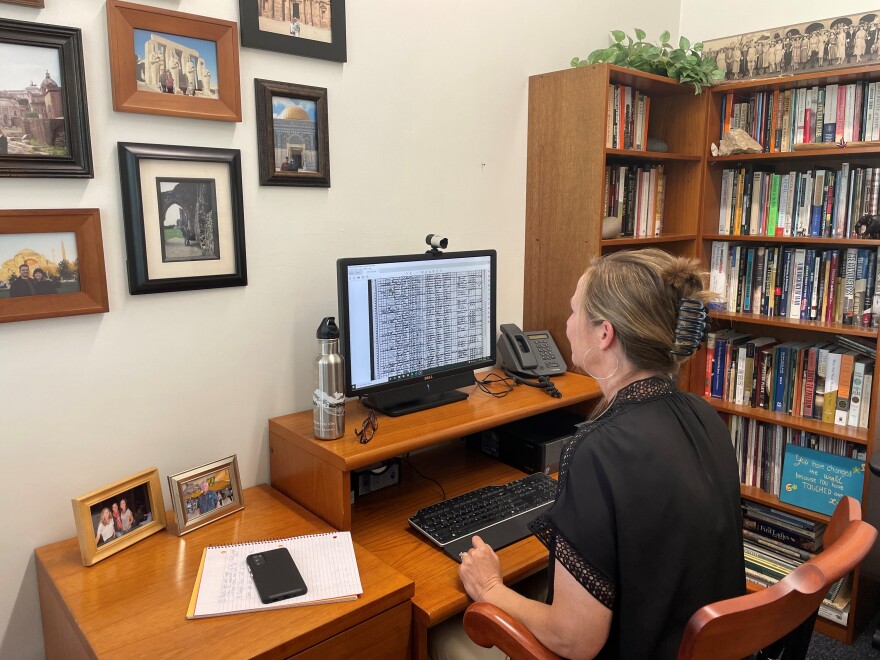

Colman’s office has cozy furniture, photos from her travels all over the world and lots of books… even though she says she’s done a recent clean out.

Colman likes that history makes her students connect with the past.

“And they understand it more. I get to spend my day talking about what I love, which is American history. So it's pretty great,” said Colman.

Besides working with students, Colman has a strong connection to the National Park Service. It started with a summer internship, and then she’s done various projects with the Park Service over the years. One was to look into early settlers in the Santa Monica Mountains. That meant going through census records.

“So as I was scrolling through, I got very used to seeing this whole column of W's for white. W. W. W. W. W. And then you can see right here this letter,” said Colman.

Colman has brought up on her computer census records from the Santa Monica Mountains in 1900. She points to a letter that is, at first, hard to decipher.

“Now, at first I didn't even know what that letter was. I couldn't quite tell. It took me a little bit to figure out what I was looking at, which was an N,” said Colman.

N for negro.

“When I came across this, it was just an immediate you know, it's like you can hear the brakes screeching, you know, what is this?” she wondered.

Colman had discovered the only Black family living in the Western Santa Monicas at that time – 1900. The head of that family was listed as John Ballard.

“And so I just… I wanted to know who they were,” she said.

And so the research started.

“I don't want to say I was obsessed. But I was very, very committed to finding out as much as I could about them,” added Colman.

Colman brought out a folder stuffed with historical records.

“A few times we have had to evacuate for fires and we've taken our marriage photos and, you know, passports and this I'm not kidding. Like this is going with us if we evacuate the house because this is… this is everything,” said Colman referring to the folder.

In it there are property deeds, certificates and old newspaper articles. Through these records that Colman has collected, we are able to trace John Ballard's life for decades.

Tracing John Ballard’s life back as far as we can

Let’s go back as far as we can. Back to the 1850s – Colman was able to place Ballard in Los Angeles, which she says is pretty astounding.

“You know, based on the census records. If you're looking at the 1850s for the City of Los Angeles, we're talking like 12 African-Americans,” said Colman.

Colman wanted to go back even further but couldn’t.

She knew from Census records that John Ballard was born in Kentucky and she had found writings about him that said he had been enslaved. Despite making a trip to Kentucky herself, Colman couldn’t find more on Ballard. She discovered, as she had anticipated, there aren’t good records for the people who had been enslaved.

“And we can only take his history back so far because his ancestors were treated as property. So, to run into that wall… Obviously, I'm a historian. I knew that… But to be in the archives and to be doing the research. Getting so frustrated and angry over that. That's when I really had that visceral reaction to what slavery meant and still means to America,” she said.

Colman can’t be certain, but she does have a theory of how John Ballard got to California.

“I kind of think this is most likely. His owner brought him here in the 1850s. Certainly the gold rush of 1849 brought a lot of folks to California,” she said.

Colman is not sure what Ballard's life was like when he first arrived in California. Although California was admitted to the Union in 1850 as a free state, slavery still existed in the state and officials mostly turned a blind eye.

Over the course of the next decade, though – the 1860s, Ballard's situation changed dramatically.

“I'm finding all of these property deeds. He's buying property from prominent citizens. He's buying property from the guy who founded USC. And selling and owning a home. And his kids are going to school here. And then shortly after that, in 1869, I've got John Ballard, and there’s maybe six others in a deed…. they bought property for a church, and they're listed as the trustees of the first African Methodist Episcopal Church,” said Colman.

Colman has records of Ballard having white and Mexican neighbors and even a Native American servant.

Then the 15th Amendment passes in 1870 giving African American men the right to vote.

“John Ballard is one of the first black men to register to vote in Los Angeles. They're putting on celebrations. They put on these balls Downtown, celebrating the end of slavery. Celebrating the 15th Amendment. I mean, they're just they're prominent citizens of this city,” said Colman.

But then things change once again for John Ballard. His wife died in childbirth in 1871. And with the building of the transcontinental railroad there was an influx of easterners who brought with them a Jim Crow mentality – many of them wanted to reproduce the same oppressive set of laws and restrictions that existed in more than a dozen southern states, laws that codified the belief in white supremacy and legally relegated Black citizens to second class status.

That led to a loss of social and economic status for John Ballard, Colman believes.

“So, I think by the late 1870s, this is just a guess financially I think he was doing very poorly. He had lost his wife. Some of his kids were moving on. Some of his kids, though, as teenagers were working in the homes of white people, which to me must have been a really bitter situation for him, because I… my sense would be that he worked so hard to give his children a wonderful life in which they don't have to be serving other people. But yet here they were,” said Colman.

So, in the 1880s John Ballard left Los Angeles for the Santa Monica Mountains. He and some of his family made a homestead next to a mountain that turns gold, orange and purple at sunset and has waterfalls cascading down it in the rainy season.

John Ballard lived here until his death in 1905.

That mountain, as you probably guessed, is what is known as Ballard Mountain today. It was renamed 105 years after John Ballard’s death.

The renaming of the mountain

The effort to rename this mountain brought a group of white folks – Patty Colman, the historian, Paul and Leah Culberg, the couple living at the base of the mountain, together with politicians and other community members.

After years of trying to get different community organizations to take up the cause to no avail, Paul Culberg finally approached his local county supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky. He cornered him at a holiday party.

“With some backup information, a picture and a map, and said, ‘You've got to hear about this’. And we started to tell him to start it and he said, ‘Stop’. He reached his pocket and he pulled out a notebook and a pencil and he said, ‘Okay go’. It was politically for him absolutely the right thing to be doing. And he jumped on it,” said Culberg.

Yaroslavsky told me, at first, he couldn’t believe the mountain had this name. He had to look it up for himself.

“So, the next day I got in my office, I got on all of the U.S. Geological Survey site. And sure enough, there it is,” said Yaroslavsky.

The former supervisor said he had no idea how to change a mountain's name but became an expert quickly.

“The renaming of it is important, but not to sweep under the rug what the original name was. And it is part of our history and shameful as it may be. And we need to acknowledge that,” said Yaroslavsky.

A plaque with the mountain’s new name was placed on the Kanan Road side of Ballard Mountain. Yaroslavsky says when he’s in the area he stops to check on it. The plaque has been defaced before.

The ancestors of John Ballard

Back at the base of Ballard Mountain, on the opposite side of where the plaque is located, Paul Culberg sits next to his wife Leah in their pool house. Paul’s handmade bird houses are dotted all over the property, which is surrounded by hills, oak trees and chaparral. For the couple, the renaming was righting a wrong but it also brought them something else.

“And as it happened, the benefit I mean, for me, the benefit was we found the Ballards,” said Culberg.

Ryan Ballard is the great, great grandson of John Ballard.

“My father was in World War II. He is an original Tuskegee airman,” said Ryan Ballard. “My grandfather, his father, Dr. Claudius Ballard, was active military in World War I. He actually was awarded the Croix de Guerre from the French army and served as a medical doctor there. And we just know that his father was William. And by extension, we know that William's father was John.”

Ryan Ballard is a special needs teacher and lives in the Los Angeles area with his family.

He has joined Paul and Leah Culberg as they sit in the shadow of Ballard Mountain. They’ve moved poolside where the wind blows gently around us.

Ryan knew his family had a long history in this region but it wasn’t until an L.A. Times article about the renaming of the mountain in the Santa Monicas appeared on the front page, did his family think – could this be our ancestor?

Ryan called his father Reginald Ballard, the World War Two veteran, who happened to be reading the paper as well that day. There was a picture on the front page of John Ballard.

“‘Yeah, I'm looking at the paper, too’. He said, ‘That fella reminds me of somebody in my family’,” said Ryan Ballard.

The Ballards ended up connecting with historian Patty Colman and the Culbergs and became friendly with all these people who spearheaded the name change.

“Then we kind of came to meet one another and have been very friendly ever since,” said Ryan Ballard.

But that re-naming is not the end of the story for him.

“This is the part that I kind of struggle with. But I'm going to say it here. Many times, people feel like, well, that's enough. See, we fixed it. But that is not true. And I would be wrong, I think, if I said that that's good enough because that's not good enough,” said Ryan Ballard.

He has been asked how John Ballard might have felt about the renaming of the mountain.

“So, I don't want to, you know, try to trivialize and say, ‘Oh, John would be all happy because we changed the name 150 years after he came’. You know, because his lineage still had to suffer. And, how do you fix that? I don't know really,” said Ryan Ballard.

John Ballard’s descendants continue to live in a country steeped in racial prejudice and injustice.

“So, this story, I think, similar to what happened with George Floyd – for me, that's very normal. But for many people, it was shocking because they had never witnessed it before. But folks in my community, that's all too normal. But for some people, they'd be shocked to know I have three sons, that I have to teach my sons how to behave so they come home at night,” said Ryan Ballard.

He says the story behind the original name of Ballard Mountain, that of slavery, racism and injustice, can often be very uncomfortable to talk about and hear about.

“It represented something absolutely horrific that people don’t want to hear about… people don't want to talk about. A lot of Black people don't want to talk about it: ‘Oh, I can't take it. I can't take it is so horrible’. Well, how horrible must it have been for the people who experienced it? So, a little discomfort on my part. I think I can endure that to ensure that it doesn't repeat itself,” said Ryan Ballard.

That is why Ryan continues to share his family’s story.

“I'm always going to make time for this because as long as I'm here and mobile and, you know, can speak relatively okay, I am going to tell the story because I think I have a responsibility to do that,” said Ryan Ballard.

Besides telling his story, here’s where Ryan think’s real change will come from.

“I personally think that to help confront racism in all of its forms. I think the answer is going to come from well-meaning white folks. I hope that that is not received offensively, but I've been asked that before and it hasn't gained much traction. But you know who's got this ball rolling? Well-meaning white folks who have become dear friends who are just kind-hearted people,” said Ryan Ballard.

Lost history waiting to be found

After the interviews the friends catch up on each other's lives. We walk down to the bottom of the garden where Leah points out a trail up the side of Ballard Mountain – it looks like a steep, strenuous but rewarding journey.

And Ryan Ballard takes me to the exact spot where he brought his family to take their last holiday photos – Ballard Mountain looms large in the background.

There is joy in making new friends as a result of this name change — but also a sense of what this mountain’s story is really about – what Ballard calls the hard and ugly truth of being Black in America.

“When we stop celebrating and taking pictures. We go back to a reality that many people wouldn't want to trade places with us. You understand what I'm saying? And that's like the hard truth. That's the ugly truth,” said Ryan Ballard.

As renamings continue throughout the U.S. – a creek here and a hollow there – historians say it’s worth remembering there’s always a story or a person behind each of these locations.

A lost story waiting to be found.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If you're looking for The One Oh One® Design Collective visit: https://www.theoneohone.com/