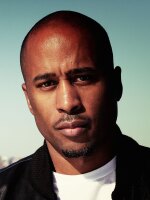

Rapper and producer J. Cole put out his second major label album, Born Sinner, this week, on the same day Kanye West officially released Yeezus. Both albums leaked before their street dates, and both were the subject of rapid-response reviews. Cole spoke to Microphone Check hosts Ali Shaheed Muhammad and Frannie Kelley about the pressures of competing for sales against one of his idols — one of the main subjects of Born Sinner — putting his own spin on classic hip-hop songs and finding songs to sample everywhere, even at the Cheesecake Factory.

Hear the audio version at the link and read more of their conversation below.

FRANNIE KELLEY: Thank you for coming.

J. COLE: Thank you for having me, first of all. Any time I get to be in this building is a crazy feeling.

KELLEY: This is a big week for you. You're really busy, huh?

COLE: Yeah, I am. I've been busy for the past couple weeks just on promo mode. But this is album release week so yeah, it's particularly crazy and hectic and you don't get a real free moment. But it's all good. It's all for the cause.

ALI SHAHEED MUHAMMAD: Do you have butterflies at this point? Like, what are you feeling like?

COLE: It's not butterflies. It's more — I'm so clueless as to what's gonna happen. Because at this point, the album has leaked, you know what I mean?

MUHAMMAD: What's your feeling about the fact that it's leaked?

COLE: It's mixed feelings. I wanted it to kind of be experienced one way, you know what I mean? That's your goal. Your plan is, you want people to go get it on release day, hear it. That's why the mixtapes were so great. It's like, we control when we press play or when we press send.

But some people are just still — some people waited, you know? And they're not gonna get it until it's officially released. So then you're gonna have a new wave of people hearing it. I haven't figured out how to experience it yet.

KELLEY: Ali waited.

MUHAMMAD: I waited.

KELLEY: He wanted to wait.

MUHAMMAD: I'm still a DJ, I'm still a record collector. And I just love getting that joint on record release day and being a part of that energy and just to, you know, feel it for the first time. But in this new position I'm in, I gotta get things early. So I waited until the last minute.

COLE: I appreciate that man, thank you. Whoever finds out how to do that — how to still maintain the physical aspect of music release but also get the experience down pat where it doesn't leak early — that's gonna be a rich person. Because there's still value in a CD, even if it's just nostalgic. People are still willing to pay. But it can't compare to a digital-only release where you can control the exact time that it'll come out, you know what I mean? So whoever finds how to bridge that gap is gonna make a lot of money.

MUHAMMAD: Well, I appreciate the record in its entirety. Just from top to bottom.

COLE: Thank you, man. That's crazy, man — coming from you, for real. Thank you.

MUHAMMAD: As an artist, explain your process. Like, you go in, you do an album. Is it like you get a concept before you begin the process or is it you just ...

COLE: Well, I can only speak to this album because my first album was not really — my second album, which is Born Sinner, is really more like my fourth because I dropped a mixtape called The Warm Up, then Friday Night Lights, and those were like albums. And then I dropped my first album. But those were such weird processes. They say you've got your whole life to make your first album.

MUHAMMAD: That's true.

COLE: But that's not true for me. That's not true for this generation anymore because I had to give so much of my life on the mixtapes, you know what I mean — on the first two. So by the time my first album came along — it wasn't a true making-the-album process. It was like, "OK, I've got these songs left. I just did these." It was more like piecing together something, as opposed to this album.

Now this album, I can speak on the process. I didn't have the concept. I just had energy and ideas and passion. And I just start spilling out beats, looping up things — sometimes I wouldn't even finish a whole beat and just spilling out words. So what I did on this album — which I think is what's gonna happen for the rest of my career is — I just start spilling things out and then wait until they take form, you know what I mean, until I see like a common thread or something. And that's what I did on Born Sinner.

KELLEY: Well, I didn't wait. I was at the listening party.

COLE: Oh, nice.

KELLEY: And I texted Ali as soon as I heard "Forbidden Fruit." I was like, "Did you know about this?" How did that happen?

COLE: That was the last song I did right before I turned in the album. I literally had two days to turn in the album, and there's one song that I did and it didn't get cleared. They would not clear the sample because Jimi Hendrix owned like a piece of the song. It wasn't even his song, but he owned a piece of the publishing from the group or something like a tiny percent, and they would not clear it. So I needed something to go in that spot, to fill that void.

It was like the point in the album where it kind of switched to like a — not a happy vibe — but it was less dark and it moved more. So for some reason, I don't know what I was doing, maybe I clicked randomly on my iTunes or maybe it was playing somewhere — I heard "Electric Relaxation." I was like, "Oh, man. What if?" You know what I mean? Like, "What if I could just do it my way?" You know what I mean? It's such a classic and people are so afraid to touch classics. And I was just like, "What if I could flip it?" So I just went and found the original sample.

It was a Ronnie Foster record. I looped up the sample and I noticed right away something I never noticed before. I guess I noticed but I was like man, the time signature on this is so wild! The fact that like y'all even put that together is crazy and then the fact that the rhymes — but then I got even more excited because I'm like, as a producer, this is gonna be fun. A. to put my flip on it and my drums on it, as opposed to like trying to recreate the same feel.

MUHAMMAD: That's why I like what you did. You didn't recreate — you didn't like try to do what was already done. You brought other parts to the sample that you caught that I was like, "Oh, nice!"

COLE: That's dope, man. To hear you say that, I'm like, alright cool. Thank you, man.

MUHAMMAD: You explained your process like you kind of shed and you bleed, but everything seems very beginning, middle and end.

COLE: No, dude, you're right. I try to — I take this seriously, you know what I mean? Like I really care.

MUHAMMAD: I can tell.

COLE: And songs like "Forbidden Fruit," where I'm flipping that sample, it's like, I care about this — I wouldn't want to disrespect the game and the culture.

It's funny because I've actually learned through the album — because of what I had to go through on my first album just to put it out, which was, I had to find this single that would work in order for the label to be like, "Alright, come on. We'll give you a release date." But I'm actually grateful for that cause it made me so much stronger.

I now possess the tools as a producer and a songwriter to really just go out and make smashes all day long. I could make an album full of smash records that got pop appeal. But my heart is in hip-hop. My heart is in telling stories. And it's like therapy for me. A lot of these verses on this album was literally like therapy. I hadn't even talked about them, I just write 'em down. So, I really do — it is well thought out because I do care about this.

MUHAMMAD: Your approach, it always seems like you — you're just going at people. I don't know if there's necessarily a person or if it's just the general feeling of like, having to prove something.

COLE: Yeah, yeah. I just always feel like I — there's always people out there that's like, doubting me, you know what I mean? Even though I do embrace the people that embrace me and I'm grateful for them. But I always feel like, man, there's still people out there that's not giving it up. And I feel like I'm doing everything the right way, you know what I mean? I'm really going out of my way to do it the right way. I'm taking very few cheats — very few cheat codes that I'm using. You know what I mean? I'm really trying to stay true to the art form and just to the craft — the craft of doing this. Because that's going to inspire the new generation to do the same thing.

MUHAMMAD: Yeah, you're not going for the cheap applause. Everything is really, really raw. It's amazing.

COLE: Thank you, man.

MUHAMMAD: And to see your growth. It's interesting to hear — from your perspective, from The Warm Up to where you are now, that you're saying, "Well, those weren't my first records." But to someone like me, I don't look at a mixtape as sort of like a warm up. I look at it at all of that as steady growth, and I was wondering, from the beginning, when you wanted to get into the music business or you wanted to make records, what was the drive?

COLE: I think it was just a passion. I found my calling — like I found something that really made me happy. I'll tell you what really drove me: the response from people. When I first started rapping, when I switched my style to more like a punch line style — this is when I'm like 13 years old — and I switched it to this real wordy — I was trying to rap like Canibus and like Eminem. It was real lyrical, real wordy and punch lines and, when I would come up with these punch lines and spit 'em in these cyphers, the minute the cyphers would be like, "Ohhh" and everybody would break away, it was a new feeling for me. It was like, "Oh, yo, you see what I just did?" I was addicted to that feeling, and I still love that feeling.

But that switched when I started making songs. And when I started making songs, I recorded a song called "The Storm" — I was 15 years old — I made the beat. And when I would play people that song, that was the new high — the response that they would give on that song was like, "Oh my god," you know what I mean?

MUHAMMAD: So you're trying to really to speak to — what's your upbringing? I'm asking for a reason.

COLE: Yeah, so I'm a military — both of my parents were in the military. My ma got out when she had me. My parents were divorced by the time I was even conscious — like I don't remember them ever being together. So my first memories of life were in this real stable neighborhood because it was military quarters. So I remember being like three ...

KELLEY: You grew up on a base?

COLE: I didn't grow up on a base, but that was my first house that I remember being in.

KELLEY: I lived on base.

COLE: You lived on base? So, you know, it's like these real ...

KELLEY: They just let you go. You can do whatever you want. It's like the most safest place in the world.

COLE: It's really safe, right? And I was thinking about this lately, or recently. You got this really safe place. I'm too young to even know what safe was, but I guess my parents' divorce was finalized or whatever by the time I was about four. So all of a sudden — my parents are divorced so my ma can't stay in this military house no more because it's only for family or for married couples.

Next thing I know, we're in this trailer park. And when I say this trailer park, this is not like Eminem 8 Mile white trash trailer park like the stereotype you're thinking about. Nah, this is the hood, like this is the projects but just in trailer park form. So, even though I was four, I was very aware of like, "Yo, this is so different from where we was just at."

MUHAMMAD: So did the environment — how was it impressionable on you? And how did it kind of like sculpt you into being?

COLE: I think it made me super observant, you know what I mean? Because I was smart enough to know that, "Man, I'm not gonna get into this." I was like four, I went to the park — my brother went to the park, too — it was our first time in the neighborhood. And this is a silly story but it just tells you where the mindset of these kids was at. This was like '89, '90. We get to the park, and I climb up the slide and they like, "Yo." I'm trying to slide down the slide. They like, "Yo, whatchu doing?" I'm like, "I'm trying to go down the slide." And they're like, "Yo, you gotta be in the gang to go down the slide." These are little kids, man. And I'm like, "Alright, whatchu gotta do to be in the gang?" They was like, "You've gotta jump off the top of the slide."

So already these kids were formulating that mentality of, "Yo, we got a little gang." Of course it ain't that serious but it tells you where they mind was at. I was smart enough to not like — as I'm growing up, I was smart enough to never really partake but I was also coming from a world where I was observant. Like, I saw the difference. I don't know if that makes sense.

MUHAMMAD: No, it makes sense.

COLE: I was looking at things from an observer's standpoint.

MUHAMMAD: So then do you liken that experience from — let's say Sideline Story to Born Sinner. It seems like you kinda went along with the gang, in a sense.

COLE: Yeah. Yes.

MUHAMMAD: And then you were able to get your own footing to understand the environment, and now with Born Sinner it's pretty much like, "I'm writing the new rules."

COLE: Exactly, yes. No, that's true. OK, it's almost like I'm observing myself on this album. And a lot of my music is just self-observation. Like telling you, "Oh man. What did I just do? How much did I just pay for this chain? Why did I do that? Wait a minute." Let me talk about that. Or like, the temptation. Let me talk about that. Let me observe myself. Sometimes in my music, I'm observing other people — friends' stories or maybe someone just in passing. But this album is a lot of self-observation and breaking down the layers of myself.

MUHAMMAD: It's really honest. It's kind of hard for me to detach the fact that I'm 42. I've been involved in the music business for a long time, you know? But in the younger generation, you guys have your own story that's amazing — the life challenges are amazing. We feel like we've gone through some things. But, no, each generation has their own. And it's because you're more — you're not shielded in the way that the generation was before you from certain aspects.

COLE: Right.

MUHAMMAD: So it's like the rawness ...

KELLEY: What do you mean? Shielded from what?

MUHAMMAD: Just any aspect of life because it hasn't unfolded yet. So it's unfolding as you're — whatever age you are, you're new in history. So anything that was learned before that people didn't know, you're getting: the good, the bad, the unknowns — all of that. Then you're growing up. It's the same thing with technology. You've got a kid who's like two years old, who's like this on the devices.

COLE: I feel you, yeah.

MUHAMMAD: I'm thinking about the fact that your music — for example, you talk about hook-ups, and it seems like random smashes and enjoying the life and — it is what it is and accepting it. But when you have "Power Trip," that song is so based in love.

COLE: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: I love the raw honesty of it.

COLE: The one thing I want to say about "Power Trip" is it's been, we like 20 years now of rappers having to be like the most coolest, most fly, most macho. Like Biggie was so cool, he could do no wrong. Biggie was what you wanted to be when it comes to being a ladies' man — or how he talked. Like Jay-Z, same thing; Mase. And even going back to Tribe — that was more of a realistic way to talk to women: "If I was working at the club / You know you would not pay." That line is such a real line. You could say that to a girl. Anybody could say that. But even that is smooth ladies' man talk.

"Power Trip" explores another side that like I feel like a lot of rappers won't show, which is, yo, what if you're just shy? You know what I mean? What if you just don't really have the balls to holler at this particular woman? What happens then? Why is nobody talking about that? Well, guess what? I'ma tell you about it 'cause I know what it's like to be that, too. I know what it's like to be that person. So it's a different level of honesty that I feel like I have been trying to bring to the game.

MUHAMMAD: You're doing it. You're beyond trying. I wanna know, who's the bass player? Who's the keyboardist? In North Carolina, was it very musical?

COLE: I didn't grow up like around like church and where people was playing.

MUHAMMAD: So what was your musical influence?

COLE: My mom and my stepfather. My stepfather brought the hip-hop side and the R&B from your Ohio Players or Marvin Gaye or whatever. But he really brought me the hip-hop side. And then you have my mom who was bringing me classic rock and folk music. I'm talking Peter, Paul and Mary. Everything from Peter, Paul and Mary to Queen to Eric Clapton and into the modern stuff — so Red Hot Chili Peppers at that time, Counting Crows, Smashing Pumpkins.

She was playing all of this and at the time, when you're a kid, I'm like, "Come on, Ma, why you playin all this?" It's not cool to me, you know what I'm saying? Like, "This is white music!" You know what I mean? "I'm too cool for that!" But one thing I'm grateful for is, nah, man, that really seeped in my pores — all of that music did. I have such a greater appreciation for all that music.

MUHAMMAD: I love the way that you married pretty much all of that. It has this alternative kind of real loungy but dark, you know, but then you got the hip-hop, the heart and then its soulful. Everything moves melodically. Even like with the — some of the chorus-y, churchy sort of parts, it just feels good.

COLE: Thank you, man. I'm grateful that I did have a wide range of like influences. I started playing violin in the 5th grade. They had a program in school where, you could get out of class to go play instruments. So I raised my hand, left out of class, me and a bunch of my homeboys, just to get out of class for that day. They asked what instrument you wanted to play and I picked the violin. And all my homeboys, they never came back — I was the only one that stayed there. Even though I never mastered it — I didn't take it too serious — I can read music now but I didn't practice enough to really master it. But just being in an orchestra every day, even though it was just a school thing, it really taught me about music — more than what I knew at the time. I didn't appreciate it. But how to count notes and how to read music and count beats or whatever so I have that background.

KELLEY: How do you listen to music? Because you sample a lot. Are you always listening? Do you dedicate a certain amount of time to work?

COLE: Yes, absolutely. I just found a — we was at Cheesecake Factory the other day and soon as we sat down, there was a song playing and I'm like, "Yo, what is that song?" I'm asking the dude like, "Yo, you got --" what's the app? Shazam? Like, "Yo, you got Shazam? Can you please find this for me?" He didn't have the app and the music was too far away, so I ran in the bathroom — this conversation's actually reminding me that I gotta go get this song — I ran in the bathroom, cause you know they've got the speakers in the bathroom too, and just wrote down as many lyrics as possible so I could Google them later. And I found the song through Google.

KELLEY: What was it?

COLE: I'm not gonna tell, so they can steal my sample.

MUHAMMAD: You can't get it out of him.

COLE: I can't give it away because then they gonna steal my sample. It's crazy though; the sample's crazy. So I'll do something like that and then I'll add that to the sample stash.

But when I'm in a zone — especially more before the deal when all I had to do was wake up and do music — I used to have to go through CDs and albums and vinyl, these days I just go online and download as many albums as possible and I'll spend three, four hours just combing through samples, putting them to the side, then another five hours making beats. Hopefully something catches and I'll start writing. If not, I finish the day with four or five beats and then come back the next day.

MUHAMMAD: What do you work on? What's your main piece?

COLE: It's simple now; it's Logic. I just got Logic and a USB keyboard.

MUHAMMAD: OK.

COLE: And some headphones, man. That's how I made "Power Trip."

MUHAMMAD: I love your production skills.

COLE: Thank you, man.

MUHAMMAD: You don't get enough credit.

COLE: Man, they don't give me no credit. Thank you, man. Maybe now that you say it, they gonna give me some credit.

MUHAMMAD: It's remarkable.

COLE: Thank you, bro.

MUHAMMAD: To me, Jimmy Jam, Terry Lewis, Barry White, James Brown, Dilla, J. Cole. You know what I'm saying?

COLE: Oh my god, I'm about to write all of that — that's so crazy.

MUHAMMAD: Because it's just so complete. It's so complete.

COLE: Thank you. Man, I work hard on it because I'm a competitor, so the same way — even though I'm a rapper first, I have an equal passion for production because I do it. I'm not gonna be bad at anything, and I want to actually be the best at anything I'm doing. So if I'm playing basketball, if I'm taking the SATs, like there's a competitive spirit behind it. With production, it's the same thing.

At first it was just like, OK, I wanna be good at this but I really just wanna make songs. I think in the past four or five years, it's gone from like, nah, I wanna show people that I can out-produce some of these producers that they — the same way I feel with the rap: I wanna show you I can out-rap your favorite rappers. I wanna show you I can out-produce your favorite producers. So I'm constantly getting better and I understand that there's always room for growth, especially in quality, sonic quality.

MUHAMMAD: Is there a battle between the producer J. Cole and the rapper J. Cole in terms of time? Because for me, production takes, I don't know, it's exploratory so I just get lost in it.

COLE: I think they have a good relationship — it's not a battle. They understand each other. Honestly they hold each other back, to tell you the truth. But it still works. The rapper side has to wait around for the producer side to make something that he agrees with. I've never gone to whoever the hot producer is, I've never gone to see him, you know what I mean? I've always just relied on myself. But imagine if I did. In a sense you could say I might be further. You know I don't know, I might have more this, more hits, blah, blah, blah. But it's a marriage that I feel like works for me. It's the way I enjoy making art — I like sitting down and making five beats; I enjoy that process. I can go two weeks without making a song and just making beats and I'll be OK.

MUHAMMAD: Let me ask you a question. There was something that you said on "Forbidden Fruit" that made me write, "What does life after death mean to you?"

KELLEY: That's funny because I have a question written down that says, "Do you go to church?" I don't know why.

COLE: Oh, wow. Well those are two — I can attack both of those questions. I haven't been to church in a very long time. It's been a couple years maybe since I went to church. But I wish I went to church more, you know what I mean? I wish I studied more religions, I wish I read the Bible, the Quran. I think as I get older, I will start to really dive into religions, just because I feel like there's truths in all of those books. Clearly. I'm saying there's truths in all of them. Not just the Bible, what is it, it's the I-Ching when they talk about the way? I used to read that and really believe it. And I still do. So as I get older, I feel like maybe I'll fall into church or like fall into some type of theology.

KELLEY: Was it a part of St. John's at all?

COLE: Yes, we did take theology courses at St. John's. Four theologies, four philosophies.

KELLEY: That's a lot.

COLE: Yeah. I actually wish I would have paid attention more in those classes. I was just caught up in college. I got good grades but like I didn't really grasp as much as I paid for.

MUHAMMAD: Some of that stuff will come back to you later on. You'll be like, "Oh! That's what that was! That's what that means!"

COLE: I look forward to that, man.

MUHAMMAD: In the song "Born Sinner," you mention Tiffany. Who is Tiffany?

COLE: Tiffany was this girl that I went to elementary school with who was the first person that I ever knew that got killed. That's why I even brought her name up in that song. Because it was the first time that somebody dying wasn't just on the news, you know what I mean? It wasn't just in a movie or something. It was somebody that I was actually in class with. This girl was here yesterday and now she's not there.

MUHAMMAD: How old were you?

COLE: Maybe second grade?

MUHAMMAD: My god. You remember the emotion of feeling everything for the first time?

COLE: Yeah. I wasn't sad. It was weird. It was a weird feeling. I felt like I was supposed to be sad, you know what I mean? I remember feeling like that. Of course I was sad like, man, this girl isn't here no more — that's gone. But I wasn't crying. I felt a pressure to cry. All the other kids was crying and I didn't feel that.

MUHAMMAD: That's pretty tragic for the youth. It seems like every other day on the news, some young kid dying. And then you see, they go to the schools and you see the kids shedding their emotions. There's a shock value and there's some — a numbness to it, like it happens all the time.

COLE: Right.

MUHAMMAD: Love the song. Just the mood of it, and everything. It kind of goes on a journey from the beginning to where it ends. And I love the "born sinner" and what do you say? "Die better than that"?

COLE: Yeah. "I'm a born sinner / But I die better than that." That line is crazy. I didn't write it. That's James Fauntleroy who wrote that line. When he did that hook, we was in London and I had those two verses over that beat but I didn't have a hook. And I happened to be in the studio with him because he was working on Rihanna.

I was like, "Yo, James. I got this joint," you know, "Let me see if you feeling it." And he was loving the raps and he was asking me the direction. I told him about that first line or that line in the first verse that says, "A born sinner was never born to be perfect." I liked the phrase "born sinner," so he went in there and knocked out this hook. As soon as he said the first line, I got chills and I knew that that would be the album title. He said, "I'm a born sinner / But I die better than that." I was like, "Oh my god!" It's the perfect — it's exactly what I was going for and what I was trying to say and the theme of the album.

MUHAMMAD: It's very heavy and I love that. It's such a heavy line and it just starts off the record that way and it ends it off.

COLE: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: You set a tone.

COLE: Thank you, man.

MUHAMMAD: I don't know what to say. It's exciting for hip-hop right now to have an album like that. Amongst — for me, I think what's been missing in the most recent aspect of hip-hop is a simple little world called love. And I think that people kind of — it may be a way society is and people are raised and are not really surrounded by love, but it's so much of a thing that you don't really reflect in it enough.

With your record, the fact that you sprinkle a lot of love into your record, because it's woven in love and it's woven in questioning these situations of life. And being young and this is what our life is: it's about money, it's about going hard to get things, it's about like, "Yo, should I be doing that?" You know, "What's better? What's out there for me?" And I think the way that you deliver it is kinda where blues artists were. Where Tupac was. Where certain writers, certain artists ...

COLE: Man, that's just — yo, you saying this, man, I'm over here like, God. Thank you, man. It's frustrating for me when the fans see what you're saying and they can't put it as well as you probably, because you studied this and you really know music. When I was a Pac fan, I ain't know why I liked him until I got older and I could process it. So the fans now, they know everything you're saying, but they can't verbalize it. But it's frustrating when, man, you got a hip-hop legend who can say that and clearly see that but then you have this area of like, tastemakers and or quote unquote tastemakers ...

MUHAMMAD: They don't count.

KELLEY: Also they got Biggie wrong. They got Outkast wrong. They got Tupac wrong. They got Tribe wrong, right?

MUHAMMAD: That's true, yeah.

KELLEY: Y'all didn't break for a long time. And that's — but all of those people come from love, also. You just gotta accept it.

COLE: That makes me feel better.

MUHAMMAD: You're gonna be good for a long time. Because that little small element, it's what we're created for. If you maintain that, you're gonna be great. And the fact that the climate of hip-hop right now — I understand being celebratory, because life may be somewhat — there's certain hardships and it's just better to kind of like get drunk and get lost and forget things. But at some point, you numb yourself out and you're not making any growth. There's no growth and you're not changing. You gotta really look at your surroundings and go, "What am I doing wrong?"

COLE: That's real.

MUHAMMAD: You know, you can't continue to blame these adversities. You gotta take control of the situation.

COLE: Yes. And I love even you bringing up that point because I've never looked at it like that. But now that you're saying it, in terms of the theme of love it's like — "Born Sinner," that's a song all about maintaining a relationship in love through all of these other hardships and when you're supposed to fail. So it's just dope — you put me on and it's helping me clarify the album.

At the beginning of the album, you hear songs like "Trouble," these songs that are way more like, not really about much. "Trouble" is me — I'm making commentary in the process but I'm really just kind of stunting and taking on this persona of being the most G'd up player: "God flow / Paint a picture like a young Pablo / Picasso / N---- sayin' / Live fast / Die young." It's more about the flow and my tone and less about anything really, you know what I mean? That's why the song is called "Trouble" because as an artist in today's climate, as a rap artist, you can easily fall into that. Like they want you to do that.

MUHAMMAD: Yep.

COLE: They want me to keep making songs like that. Which I will, because that's a side of me. But I'll never fall all the way over there, which is what they want you to do.

MUHAMMAD: Exactly.

COLE: And the album ends on all of these love records, you know what I mean? "Let Nas Down" — that's a song expressing nothing but love for my idol, for one of my idols. "Crooked Smile," that's a song all about loving yourself first and foremost.

MUHAMMAD: Yo, it's such a pleasure, such an honor to have you up in here. Just continue doing everything that you're doing.

COLE: Thank you, brother. I will, man, I will. I'm just excited, man. You even saying these things. Man, it's just an honor, a privilege. I don't even know what to say, bro. You're breaking it down for me. I'm like, damn. Thank you.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.